Muhammad Assad

March 01, 2026

By | Muhammad Assad

Music, art, and literature are three important pillars of every culture, helping people to express their feelings, talk about social problems, and raise voices against the miseries of the marginalized sections of society. Art, music, and literature are not just the repository of society’s collective memory, but they also play an important role in changing opinions, instilling new ideas in people’s minds, and can contribute to resisting the threats that undermine the peace and just values of society. The Pashtun Culture, although rich in the three aforementioned elements, saw continued proxy wars and struggle for power between external and internal actors in Pakistan’s northern parts over the last few decades. These wars have affected almost every aspect of Pashtuns lives but music, art, and literature have been affected the most. This writing, however, will primarily focus on the role played by music and musicians in the tribal Pashtun belt of Pakistan during the pre-and-post-Taliban era, along with the censorship and oppression of Pashtun music and musicians, respectively, during Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP’s) rule in the region.

Music and musicians have always been an important component of the tribal Pashtun culture and society but the rich cultural traditions of playing music, dance, poetry recitals, and other social gatherings were badly affected due to the decades-long armed conflict in the region which have not just stopped the evolution and development of these cultural traditions and institutions in the area but have also imposed extremist and foreign interpretations of Islam on the Pashtuns of this area, leaving no room for such cultural traditions to exist.

Music has deeply ingrained itself into the fabric of Pashtun society, becoming a constant presence whether in times of joy or sorrow, war, or peace. Unlike other societies, in Pashtun society, music is not just played on joyful occasions such as marriages but even on occasions like deaths, when mostly elderly women sing sorrowful tappay (a popular two-liner literary genre of Pashto folk poetry) on the death of their dear ones while mourning. Such practices were predominately popular in areas like Kurram, where some people used to beat drums and play other indigenous musical instruments during Azadari (religious mourning in the memory of the martyrs of Karbala) and on the passing of their loved ones. Not only has music been affected in Pashtun societies due to conflicts and extremism, but individuals and families associated with the music industry have also been victims of marginalization/discrimination. Even before the Taliban took over the area, musicians were labeled with derogatory terms like “Daman” (people having no honour). To capture the dilemma and contradictory relationship between Music and Pashtuns, there's a Pashto saying that encapsulates this sentiment: "A Pashtun loves the music but may not appreciate the musician."

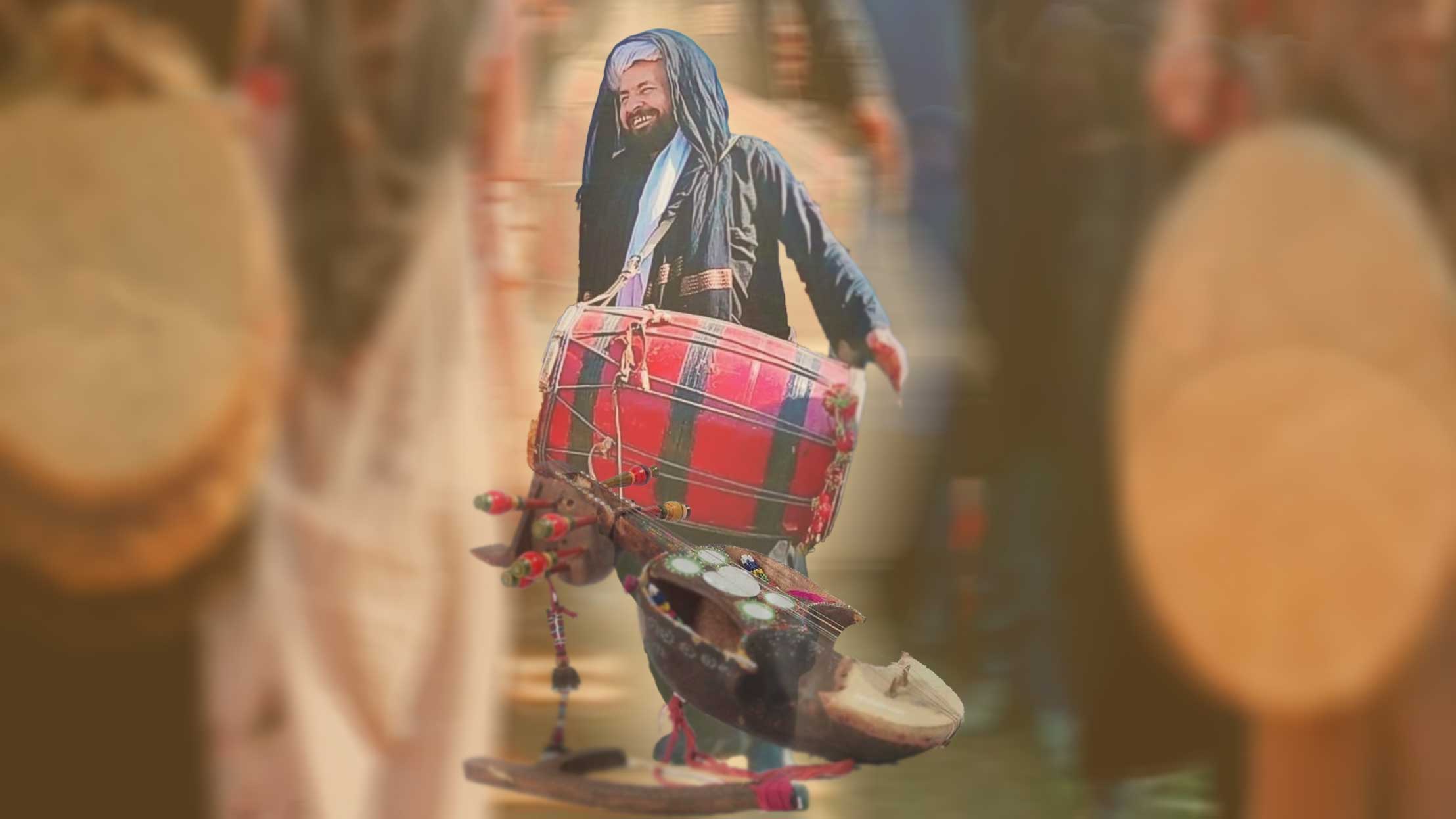

To understand the role and status of musicians in tribal areas like Waziristan before the Taliban came to power, let’s look at the role of “Dum”, an individual who use to play an indigenous form of drums, locally known by the term “Dhol”, while singing or dancing.

The word “Dum” is singular of the aforementioned derogatory term “Daman” but is widely used for Dhol players, although the actual word for Dhol player in Waziristani dialect of Pashto is “Dhol-Zan”. Dhol, Dum and dance are among the most crucial components of Tribal Pashtuns’ social life because the two can be found in almost every activity of tribal Pashtuns.

Zarray Mehsud, the renowned drummer of Waziristan, passed away in December 2022

In the historical context of Pashtuns' tribal society, that has been characterized by weak governmental institutions then as it is now, the community took charge of various activities. The Dhol and "Dum" played crucial roles in facilitating these communal efforts. For instance, when there was a need to gather people for announcements, the "Dum" would rhythmically beat their Dhol to alert and inform the entire community. Similarly, when community mobilization was required, whether for Cheegha (a collective response to danger), canal repairs, or any other communal endeavor, the "Dum" took on the responsibility of informing individuals within the society through the rhythmic beats of his Dhol.

The sarinda is a stringed folk musical instrument similar to the Sarangi, lutes, and fiddle

In times of inter-tribal conflicts, the "Dum" assumed the role of a messenger, possessing the unique privilege of entering enemy territory. Moreover, during occasions like marriages and festivities, he multitasked as a barber and a cook for the tribe, showcasing the versatility of his contributions to community life.

Besides these social hurdles, before the 1980s, music and musicians had relatively greater space and role, both in the tribal and in relatively urban Pashtun societies. But the soviet intervention of 1979 and the cold war in Afghanistan and the arrival of the US and its allied forces in the region after 9/11, brought dramatic changes in Pashtun’s social life by directly and severely effecting the secular tribal structure of Khyber PakhtunKhawa and Ex-FATA, particularly Waziristan.

In order to increase the role of Islamic clergy and the fundamentalist interpretation of Islam, there was a systematic targeting of Pashtunwali, along with secular institutions such as Hujra, and key figures like Malak (community elders) and musicians. This deliberate effort aimed to reduce the influence of these traditional institutions and individuals, as their roles directly conflicted with the objectives of religious clergy. They posed a significant obstacle to the broader project of Islamization within Pashtun society.

Other than religious reasons, the significant role played by the Dhol in community mobilization was a key factor. The Taliban, recognizing its potential impact specifically prohibited the beating of the Dhol. This restriction stemmed from their apprehension that the rhythmic beats of the Dhol could serve as a powerful tool for community mobilization, posing a potential threat to their authority.

But unfortunately, besides playing such an important role, he (the Dum) was not given due respect in society. No one liked to be called “Dum” or to be married in the family of a “Dum”, because in a society where a weapon is considered a man’s jewelry and honour, “Dum” was the only unarmed man, so he was and is still considered inferior to others.

For this specific reason, Gohar Wazir, a senior journalist from the region, revealed that some drum players in Waziristan secretly supported the Taliban's ban on beating the Dhol. Despite the undeniable importance of their role, these individuals faced societal disapproval, prompting a desire to switch professions. They aspired to garner the same respect enjoyed by others in Pashtun society, making them willing adherents to the ban imposed by the Taliban.

Aside from Dhol players, Waziristani musicians, situated in the epicenter of terrorism, also bore the brunt of its impact. However, due to stringent restrictions on media coverage within this valley, only a limited number of incidents related to music censorship could be reported. The limited data available on music censorship in Waziristan and the adjoining areas of KP has primarily been gathered through oral accounts obtained by engaging with local musicians, poets, journalists, activists, and other relevant sources. The subsequent narrative sheds light on some of the instances of music censorship during the Taliban's rule in the region.

For instance, before the 9/11 incident, Kamal Mehsud, a known singer from South Waziristan singing Pashto, Saraiki, and Urdu songs, was forced to leave Waziristan as he was continuously receiving death threats from the TTP after the Pakistan army’s media wing, the Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR), distributed his music album, centered on themes of peace, free of charge in Waziristan. Unfortunately, Mehsud met a mysterious death in Islamabad, succumbing to burn injuries resulting from a fire that broke out in his home.

Kamal Mehsud, a renowned singer from Upper Waziristan, passed away in Islamabad in January 2010. Among his most popular songs is "Tum Chale Aao Paharon Ki Qasam," later reproduced by Ali Zafar.

It is worth noting that Mehsud valiantly refused to abandon his musical pursuits despite persistent death threats and resisted the influence of the TTP until his passing.

Abdur Rehman Darpakhel, another singer from North Waziristan who migrated to the adjacent Bannu city after he refused to abandon his music profession during the Taliban rule in Waziristan, continues to pursue his musical profession despite the adverse conditions.

Similarly, in North Waziristan, Nazir Ahmad Nazir, a famous “Lughati” singer who sings impromptu poetry, was forced to leave his profession and move to Abu Dhabi for work.

Singer Musharaf Bangash was kidnapped by a local Taliban commander from the Hurmaz village in Mir Ali and was released after negotiation. Another singer Rehman Shah Betani was kidnapped twice and later forced to leave his village Jandola, Tankm because of his uncle, who was affiliated with the Taliban.

“They tortured me, beat me severely for two weeks, and forced me to take an oath that I would give up singing,” said Betani.

On the other hand, Rahmatullah Darpakhel, another singer from North Waziristan, abandoned his singing career and adopted a religious life. He joined the Taleeghi Jamat but continued writing religious poetry.

Maqsood Maseed, from Upper Waziristan district, is a young singer and Musician. He is the founder of Sandaara School of Music & Arts in Islamabad.

In Waziristan and other areas of the erstwhile FATA, a blanket ban on any business or activity related to music was imposed, mirroring the broader restrictions observed in other regions of KP and Pakistan. Several music centers in Ex-FATA became casualties of this stringent policy, either being forcibly shut down, bombed or coerced into selling Jihadi anthems and other propaganda materials associated with the Taliban.

Places like the Abdul Wali Music Centre in Sararogha Bazar, Noor Aslam Music in SpinKai Raghzai of South Waziristan, and Said Wali Music Centre in North Waziristan were compelled to either sell militant propaganda or face closure. Even well-known shops like Gul Zaman Music Centre in Tank had to shut down, while its branch in Dera Ismail Khan fell victim to a militant bombing in 2007.

The aforementioned events not only highlight the severity of censorship and the challenges confronted by artists but also show how these creative individuals bravely resisted the strict rules imposed by the Taliban and championed peace through their artistic contributions.

The enduring wounds of the ongoing proxy wars are not only evident in the historical record and the vanishing traditions of Pashtunwali, such as the Bragai Attan (mixed-gender dance), playing of the Dhol, and the institutions of Jirga (traditional dispute resolution) and Hujra (community center for social gatherings), but these facets of the Pashtun culture have either been reshaped, weakened, or completely eradicated.

The bad effects and lasting marks of these proxy wars go beyond what you can see in tangible aspects and are also seen in Pashto literature, especially in poetry.

Writers, especially poets, play a crucial role in both shaping and preserving culture. Their sensitivity to cultural shifts is heightened, as they not only contribute to cultural development but also bear the responsibility of safeguarding valuable elements of their heritage.

The previously dominated topics in Pashto literature such as love, the beauty of the beloved, unity, forgiveness, and peace were replaced by topics such as violence, hate, blood, war, suicide attacks, helicopters, drone attacks, and the TTP. Some examples, shared by researchers Wasai Jawad Ullah and Abida Banos in their paper, sheds light on the transformation of Pashto poetry, which can be seen in the following couplets:

(a): “Stragay day drone na kamay na di: Warta Talib Talib kedam eera ye krhama”

(Your eyes are not less destructive than drones: I behaved like the Taliban and perished)

(b): “Za laka B-52 yo ghar bal dar pasay garzama: Ta shway Osama Ashna heis pata de na lagi”

(Like a B-52 plane, I search one mountain after another. O my beloved, you, like Osama, have entirely disappeared)

Talking about this shift in Pashto literature, veteran Pashto Poet Rahmat Shah Sael said during a seminar, "Poets are inspired by what is happening in the world. Their imagination absorbs it, which is why Pashto poets are writing about violence in one way or another”.

There is another fascinating aspect of the transformation in poetry is the censorship of musicians and music. Despite the Taliban's prohibition of instrumental music in Islam, they developed their own form of music known as Jihadi Tharana.

In Jihadi Tarana (also known as Nasheed), the poets express their support for those fighting in the name of Islamic Holy war (Jihad) and instigate people to join them in the fight and get rewards in the hereafter.

According to sources, aside from religious motivations, one of the main reasons the Taliban banned other forms of music was to create a parallel market for their Jihadi Tarana and Nazam. This move was an effort to establish an alternative form of poetic representation amid the influence of religious politics in Waziristan.

Given the current surge in terrorism in the Pakistani Pashtun region following the fall of Kabul, it will be interesting to observe the responses of Pashtun artists and how they navigate and cope with the ongoing wave of terrorism.

Considering the tumultuous history of KP, it becomes crucial to assess how religious insurgents may attempt to censor artistic work, especially with the prevalence of modern communication channels such as social media, FM radios, governmental and non-governmental TV channels, and web and satellite TV channels.

These contemporary means of communication empower artists to connect with their audience from various locations, providing a platform that can potentially circumvent censorship by both governmental and non-governmental entities. The evolving landscape of communication may influence how Pashtun artists express themselves and share their work in the face of the current challenges posed by terrorism in the region.

Disclaimer: Views expressed by the writer in this blog are his own and do not necessarily reflect The Khorasan Diary's policy.